EXCERPT: ‘The Trojan Heritage’ By Mal Florence

A pictorial history of USC Football

Mal Florence

3/27/2020

(From 1951 until his death in 2003, Mal Florence covered sports in Southern California—particularly USC football—for the Los Angeles Times. But he observed Trojan football since he watched his first game as a youngster in 1934. He then enrolled at USC during World War II, where he even played halfback sparingly in 1946. He was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame’s media wing in 1995.)

(In 1980, he wrote a book about USC’s football history, “The Trojan Heritage.” At the time, he granted USC permission to run portions of his book in the USC football media guide. Excerpts appear below, updated after his passing.)

* * *

The Trojan football tradition. It means many things:

~The teams. The Thundering Herd teams of the late 1920s and 1930s, the war babies of the mid-1940s, the “I” formation-styled national champions of the 1960s and 1970s, and the current rebirth in the 2000s.

~The Rose Bowl, USC’s second home.

~The tailback. The slot that has evolved into the position in college football. A glamour figure with names like Morley Drury, The Noblest Trojan of Them All in the late 1920s, and Russ Saunders, Gus Shaver, Orv Mohler, Cotton Warburton, Amby Schindler, Grenny Lansdell, Frank Gifford, Jon Arnett, Mike Garrett, O.J. Simpson, Anthony Davis, Ricky Bell, Charles White, Marcus Allen and Reggie Bush.

~The coaches who have made an indelible impression on the game. Gloomy Gus Henderson bringing national recognition to USC; Howard Jones earning national respect with his Rose Bowl-winning teams and national champions; John McKay altering the concept of offensive football with his innovative “I” formation; John Robinson achieving that awesome balance of power running and productive passing, blended with stifling defense; and Pete Carroll, whose enthusiasm and competitiveness drove an aggressive defense and innovative offense.

~The rivalries. The one with Notre Dame that began in 1926 and has grown into the most prestigious intersectional confrontation in the country. Then there’s the one with UCLA, in which the outcome not only rewards the winner with bragging rights for the city, but also usually means a Rose Bowl berth.

~The games. The 16-14 victory over Notre Dame at South Bend in 1931 and the ensuing ticker tape parade in Los Angeles for the conquering heroes. The stunning 7-3 victory over Duke in the 1939 Rose Bowl. O.J. Simpson’s climactic 64-yard TD run that beat UCLA, 21-20, in 1967... and on and on.

~The Coliseum. USC’s home since 1923. Here the Trojan horse, Traveler, gallops around the track as the USC band stirs the crowd with its famous fight song, Fight On.

All of this is USC football. There’s nothing like it.

* * *

In 1944 Harry C. Lillie, an attorney, supplied missing information on USC’s first football team in 1888, eight years after the small Methodist school was founded in 1880.

USC was undefeated in 1888 in a two-game schedule. How fitting this was for a school which has had almost unparalleled success in athletics—football, of course, and 70 men’s NCAA championships, more by far than any other university.

Lillie, a 125-pound end on the first ragtag USC team, said:

“The only available opposition was a club team which carried the name of Alliance. Our first game was Nov. 14, 1888, right at the university and we won by a score of 16-0.

“In those days a touchdown scored four points, with the play which now corresponds to the conversion after touchdown adding two more points. A field goal scored five points, a safety scored two.

“The second game against Alliance was played more than two months later on Jan. 19, 1889, uptown on a vacant field bordered by Grand, Hope, Eighth and Ninth streets. The club team had improved considerably and we managed to score only a single touchdown to win, 4-0.”

Frank Suffel and Henry H. Goddard were playing coaches for this first team which was literally put together by quarterback Arthur Carroll. He volunteered to make the pants for the team. Appropriately, Carroll later became a tailor in Riverside.

The growth of USC and its football program coincides with the growth of Los Angeles, which had been founded only 99 years before the cornerstone was laid at the university in 1880 in an uncultivated mustard field. At the time, Los Angeles still retained characteristics of its earlier pueblo days.

American football at the turn of the century was a combination of rugby, soccer and pure mayhem. The rules provided for a playing field of 110 yards in length, exclusive of the end zones, and games were played in 45-minute halves with a 10-minute intermission. Intentional tackling below the waist, a fundamental and coached procedure now, was judged a foul then, just like unnecessary roughness.

USC fielded another team in 1889 (without a coach) and encountered its first collegiate opponent, St. Vincent’s, now known as Loyola Marymount. The Methodists or Wesleyans (the name Trojans would come later) thrashed St. Vincent’s, 40-0, and then beat a Pasadena club team which featured the dreaded Flying Wedge, 26-0.

So far, so good. A pair of two-game seasons and USC was undefeated, untied and unscored upon.

Then, because of student apathy and some financial problems, USC didn’t have a team in 1890.

A pattern developed in which USC, still coachless, would play a one- to four-game schedule—without much success—until 1897 when Lewis Freeman became the school’s first non-playing coach. Not only did he outfit the team in sharp, new uniforms—turtle-necked shirts with “USC” inscribed on the front, knee-length pants and ankle-high shoes—he produced a winning team with a then-representative schedule.

USC, under Freeman, won five of its six games, losing only to the San Diego YMCA, 18-0. Freeman then moved on, but the Methodists continued their winning ways, recording a 5-1-1 record in 1898—losing to and being tied by Los Angeles High School.

It was during the late 1890s and the early 1900s that USC developed a rivalry with neighboring Occidental and Pomona, the early stand-ins for Notre Dame, California and Stanford.

The year 1904 marked the arrival of Harvey Holmes, the first salaried USC coach. He stayed four years, compiled a record of 19 wins, five losses and three ties and expanded USC’s schedule to 10 games in 1905, including a first meeting with Stanford. USC lost that game, 16-0, as one of the West Coast’s most prestigious rivalries began. The teams wouldn’t meet again in football until 1918.

Major college teams do not schedule too many “breathers” today because of financial considerations. But USC wasn’t thinking of the gate when it padded its 6-3-1 record in 1905 with victories over the likes of the National Guard, Whittier Reform and the Alumni.

USC continued to play football in 1908 under coach Bill Traeger. In 1909 and 1910 the team was under a coach who was to become famous in another sport.

Dean Bartlett Cromwell was called the “Maker of Champions” during his 40 years at USC—track and field champions, that is. A legendary figure in track and field, Cromwell’s teams won 12 NCAA titles, including nine in a row (1935-1943).

As a football coach, Cromwell had only modest success with 3-1-2 and 7-0-1 records in 1909 and 1910 and later a three-year record of 11-7-3 when he served as USC’s football coach from 1916 through 1918.

Between Cromwell’s first and second terms as football coach (along with a two-year tenure by Ralph Glaze, 1914-15), USC decided to move up in class athletically.

Rugby, as played by California and Stanford, was USC’s game in 1911 and a school spokesman said, “We are looking for a foothold on an athletic ladder that will carry us, we hope, to a level of competition to the proportion of our ambitious, restless, growing young institution.”

The results were disastrous. USC was badly outclassed for three years (1911-13) by more experienced rugby teams. It suffered financial reverses as well.

But all was not lost in this departure from American football. The Methodist school that was founded in a mustard field got a nickname that would identify it and its students and alumni glamorously for years to come.

Nicknames were popular in the early 1900s, but the school didn’t care much to be called Methodists or Wesleyans. So Owen R. Bird, a sportswriter for the Los Angeles Times, came up with a nickname that was to endure. It was Bird’s belief that “owing to the terrific handicaps under which the athletes, coaches and managers of the university were laboring and against the overwhelming odds of larger and better equipped rivals, the name ‘Trojan’ suitably fitted the players.”

When USC began playing football again in 1914, it also resumed its relationship with Occidental and Pomona. But the Trojans wanted to be known beyond the limited confines of Bovard Field so they began to schedule “big-time” foes such as St. Mary’s, Oregon and California.

USC split with California in 1915, winning, 28-10, and losing 23-21. Another traditional series was inaugurated.

World War I put a damper on USC’s athletic ambitions and Troy played a restricted schedule from 1917 through 1919.

USC had some outstanding players during its formative years, athletes such as Elwin Caley (whose 107-yard punt return in 1902 on a 110-yard field still stands as a school record), Hal Paulin, Arthur Hill, Roy Allan, Court Decius, Fred Kelly, Fred Teschke, Rabbit Malette, Tank Campbell, Turk Hunter, Dan McMillan and Herb Jones. But the Trojans wouldn’t become nationally recognized in football until the 1920s.

* * *

Elmer C. (Gloomy Gus) Henderson has the best winning percentage, 45-7 (.865), of any coach in USC’s history. More importantly, Henderson, in his six seasons at the school (1919-1924), achieved national recognition for USC and established the format for successful teams of the future. Under Henderson, USC recorded some historic firsts:

· Appearing in the Rose Bowl in 1923 and beating Penn State, 14-3.

· Winning 10 games in a season twice, along with an undefeated season in 1920.

· Moving out of Bovard Field, where a turnaway crowd would be 10,000, to play in the vast Memorial Coliseum, where crowds of 70,000 would become routine for Trojan games.

Henderson was the first USC coach to recruit aggressively and he persuaded talented Southern California athletes to stay home and attend USC rather than to pursue their education at California or Stanford.

He also was an on-the-field innovator. His spread formations were copied by coaches and some elements of his offense are used today by college teams and the NFL.

“Gloomy Gus” was a well-known cartoon character of the era and Henderson was saddled with that nickname by Los Angeles Times sportswriter, Paul Lowry, because of the way he poor-mouthed the Trojans’ prospects before a game.

USC had a 4-1 record in 1919, went undefeated in 1920 and was 10-1 in 1921 and again in 1922, two seasons in which the Trojans outscored their opposition, 598 to 83.

USC had a 6-2 record in 1923 which included the first football game ever to be played in the Coliseum—a 23-7 win over Pomona on October 6—and a later Coliseum game, a 13-7 loss to Cal that attracted 72,000 fans and sent a signal to Easterners that West Coast football had really caught on.

Henderson had a 9-2 record in his last season at USC in 1924, a year that featured intersectional games with Syracuse and Missouri, both of which the Trojans won.

During his tenure at USC, Henderson recruited and developed such outstanding players as Chet Dolley, Harold Galloway, Johnny Leadingham, Charley Dean, Roy (Bullet) Baker, Gordon Campbell, Andy Toolen, Lowell Lindley, Hobo Kincaid, Indian Newman, Hobbs Adams, Hayden Phythian, Holley Adams, Norman Anderson, Otto Anderson, Johnny Hawkins, Hank Lefebvre, Eddie Leahy, Manuel Laraneta, Butter Gorrell, Jeff Cravath and Leo Calland.

Two of Henderson’s sophomores on the 1924 squad, guard Brice Taylor and quarterback Mort Kaer, would later become USC’s first All-Americans. Henderson is credited with recruiting Morley Drury, who would become known as the “Noblest Trojan of Them All.”

Despite his record, Henderson was fired after the 1924 season, some said because he went 0-5 against California during his tenure.

* * *

College football history might have been changed radically if Notre Dame’s Knute Rockne had become USC’s coach following Henderson’s release before the 1925 season. Such an idea came close to becoming a reality. Gwynn Wilson, the USC graduate manager in the 1920s, remembers:

“Rockne came to USC for a football seminar and we saw a lot of him. We didn’t have a coach and we talked to Rock about the job. He agreed to come, subject to getting a release from Notre Dame. Mrs. Rockne had fallen in love with Southern California. We had hopes but they (Notre Dame) talked him into staying. Maybe it was better that Rock stayed there and we got Jones.”

Howard Harding Jones. The Headman. Responsible for bringing national recognition to USC when the East and Midwest were considered the twin citadels of college football.

His approach to the game was straight-forward yet intricate—power football, the single wing. Opponents often said they knew where the Trojans, under Jones, were coming, but still couldn’t stop them. Jones’ teams became known as the Thundering Herd, running (seldom passing) roughshod over some of the nation’s best teams.

Before Jones came to USC, the school had not produced an All-American or won a national championship. During his 16 years as USC’s coach, Jones developed 19 All-Americans, won national championships in 1928, 1931, 1932 and 1939, had undefeated seasons in 1928, 1932 and 1939, won eight Pacific Coast Conference titles and was undefeated in five appearances in the Rose Bowl. His overall record was 121-36-13 (.750) and his teams had seven seasons in which they won nine or more games.

It was during Jones’ regime, in 1926, that the USC-Notre Dame rivalry began, a rivalry now esteemed as the most prestigious intersectional series in the country.

If it had not been for the persuasiveness of a young bride in 1925, the Trojan-Irish series may never have been.

Wilson and his bride, Marion, got on the Sunset Limited train to Lincoln where Notre Dame was going to play Nebraska. Mission: a USC-Notre Dame home-and-home series. Wilson didn’t get to meet with Rockne though, until after the game when they all got on a train to Chicago.

“He told me that he couldn’t meet USC because Notre Dame was traveling too much,” Wilson said. “I thought the whole thing was off but as Rock and I talked, Marion was with Mrs. Rockne, Bonnie, in her compartment. Marion told Bonnie how nice Southern California was and how hospitable the people were.

“Well, when Rock went back to the compartment, Bonnie talked him into the game. But if it hadn’t been for Mrs. Wilson talking to Mrs. Rockne, there wouldn’t have been a series.”

Jones developed the prototype of the modern tailback. His tailback, called the quarterback in the Jones’ system, not only carried the ball 80 or 90 percent of the time, but also passed, punted and played safety on defense.

These running backs had a regal quality to their names: Morton Kaer, Morley Drury, Russ Saunders, Marshall Duffield, Gaius (Gus) Shaver, Orville Mohler, Homer Griffith, Irvine (Cotton) Warburton, Ambrose Schindler and Grenville Lansdell.

There was the great blocking back, Erny Pinckert, and later Bob Hoffman. The linemen of the 20s and 30s were the best of their day—Brice Taylor, Jesse Hibbs, Nate Barragar, Francis Tappaan, Garrett Arbelbide, Johnny Baker, Stan Williamson, Tay Brown, Ernie Smith, Aaron Rosenberg and Harry Smith.

Jones made an immediate impact at USC. His first team in 1925 had an 11-2 record. The Trojans were 8-2 in 1926, 8-1-1 in 1927, 9-0-1 in 1928, 10-2 in 1929 and 8-2 in 1930. After a season-opening loss to St. Mary’s in 1931, the Trojans didn’t lose another game until Stanford beat them, 13-7, in 1933—a 27-game unbeaten streak.

Trojan old timers still argue about which team was Jones’ best. Some say it was the 1929 team that destroyed Pittsburgh in the Rose Bowl, 47-14, even though USC lost two regular season games. Others contend it was the 1931 club that rebounded from a loss to St. Mary’s to go undefeated the rest of the season, including the historic 16-14 upset of Notre Dame at South Bend on Johnny Baker’s late field goal.

For the purists who say that the record is the only way to measure the worth of a team, it’s difficult to dispute the credentials of the 1932 team, which went 10-0 and allowed its opponents to score only 13 points.

As usually happens to any coach who has a long association with a single school, Jones had some down years, from 1934 through 1937.

USC rebounded with a 9-2 record in 1938, including a 7-3 Rose Bowl victory over Duke in which fourth-string quarterback Doyle Nave came off the bench in the final minutes to throw four consecutive passes to end “Antelope” Al Krueger, the last for the touchdown. The Blue Devils went into the Rose Bowl undefeated, untied and unscored upon.

Some insist that Jones’ last great team in 1939 was his best. USC was unbeaten, but tied by Oregon and UCLA, in 10 games. The Trojans climaxed the season with Jones’ final Rose Bowl victory, 14-0, over an unscored-upon Tennessee.

Jones died of a heart attack July 27, 1941, at the age of 55. The Trojans would have some strong teams in the next 20 years under four coaches, but they wouldn’t win another national championship until the John McKay era.

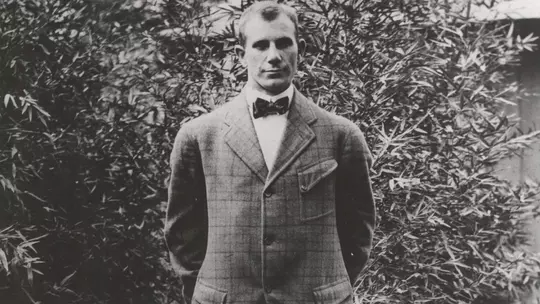

A Yale man and a former All-American at that school along with his famous brother Tad, Jones was already a competent coach when he came to USC in 1925 (he had coached at Syracuse, Yale, Ohio State, Yale again, Iowa and Duke). After a season at Duke, Jones became USC’s coach. Some say he got the job on the recommendation of Rockne.

The 1928 season marked USC’s first victory (27-14) over Notre Dame, after Rockne had tagged Jones with one-point defeats in 1926 and 1927.

Jones had a remarkably consistent record from 1925 through 1933, never losing more than two games in a season and establishing USC’s winning tradition in the Rose Bowl.

Jones believed in and coached power football. Although his Thundering Herd teams rolled up yardage and scored as many as 492 points as early as 1929, some critics incessantly carped that USC’s offense was unimaginative.

Jones added wrinkles to his offense, to be sure. He made good use of a wingback reverse and a surprise passing attack, demonstrated to near-perfection in the 1930 Rose Bowl when Russ Saunders threw three TD passes to beat Pittsburgh.

Still, it was the running game with flawless execution that was the trademark of Jones’ best teams. Rules discouraged passing during Jones’ heyday because a pass had to be attempted five yards behind the line of scrimmage and a team couldn’t throw two incomplete passes in one series. Otherwise, it would incur a five-yard penalty in both instances.

So run the Trojans did. Drury. a workhorse in the backfield, became USC’s first 1,000-yard rusher (1,163) in 1927. Amazingly, the Trojans wouldn’t have another 1,000-yard runner until Mike Garrett (1,440) in 1965.

Mort Kaer, USC’s first All-American tailback, gained 852 yards in 1926; Saunders had 972 in 1929; Orv Mohler and Gus Shaver accounted for 983 and 936 in 1930 and 1931, and Cotton Warburton gained 885 in 1933.

All of these backs averaged better than five yards per carry with considerably fewer attempts (excepting Drury’s 223 in 1927) than the modern-day USC tailback.

Years later, Willis O. (Bill) Hunter, the USC athletic director when Jones was hired in 1925, said succinctly: “I’d have to say that all of us hitched our wagon to a star, and Howard Jones was that star. He made all of USC’s later success possible.”

* * *

It would not be precise to say that USC football was in limbo in the 40s and 50s. The Trojans went to the Rose Bowl five times during that time span and such players as Ralph Heywood, John Ferraro, Paul Cleary, Frank Gifford, Jim Sears, Jon Arnett and Marlin McKeever were honored as All-Americans.

There were also some fairly strong teams in this era—Jeff Cravath’s war babies in the mid-40s and also his 1947 team, Jess Hill’s once-beaten 1952 team and Don Clark’s 1959 club.

But the Trojans had established high standards under Jones and fans of the school in the 40s and 50s thought in terms of national championships and took conference titles for granted.

Measured against the Thundering Herd days when overall only a loss or two in a season was tolerated, the 40s and 50s were a disappointing period for Trojan buffs. Sort of a waiting period. The Trojans didn’t win a national championship in this span and Notre Dame took charge of its series with USC.

Succeeding Jones was Justin M. (Sam) Barry, who had been a valued assistant for Jones. Barry had close ties with Jones. He became basketball and baseball coach at Iowa on Jones’ recommendation. Later, Jones brought Barry to USC to serve in the same capacity in addition to his assistant football coaching duties. Barry turned out winning baseball and basketball teams at USC and he was responsible for a major rules changes in the mid-30s—the abolition of the center jump.

Barry was under pressure in succeeding the legendary Jones and won only two of nine games with one tie in 1941.

When the dismal season ended, Barry was called into military service and President Rufus B. von KleinSmid and athletic director Bill Hunter began looking for an interim coach. The choice was Newell (Jeff) Cravath, a former Jones assistant and a defensive center for the Trojans from 1924 through 1926.

Cravath was coaching at the University of San Francisco in 1941 and his Dons had the highest scoring team on the West Coast. He had previously coached at Denver and in the junior college ranks.

He broke with the past and provided USC with a new offensive look in 1942. Howard Jones’ single wing, with the quarterback carrying the ball almost every play, was put in mothbalIs.

The “T” formation, popularized by Stanford’s Rose Bowl team in 1940, was in vogue and the Trojans were now in the “T”—with four backs, not one, handling the ball.

But USC had only moderate success in 1942, winning five and losing five with one tie.

By 1943 the country’s war effort was in full gear and, because of travel restrictions, teams generally played teams in their own area. But USC football flourished during World War II because Cravath was able to recruit on his own campus. Navy and Marine training programs were set up at the school and some athletes who had played at other schools were transferred to USC. Moreover, the PCC voted to waive the peacetime regulation barring freshmen from varsity competition.

Cravath had an outstanding record during the war years, 23-6-2. His 1944 team was undefeated with two ties. USC made three straight appearances in the Rose Bowl. In 1943 USC played Washington at Pasadena in the only matchup of West Coast teams in Rose Bowl history. Jim Hardy threw three touchdown passes to tie Russ Saunders’ record as USC won easily, 29-0.

USC had an even better team in 1944. With Hardy leading the way with his play-calling and passing, Troy concluded an unbeaten season by defeating Tennessee, 25-0, in the Rose Bowl. Jim Callanan scored the quickest touchdown in Rose Bowl history when he blocked a Tennessee punt and took it in with only 90 seconds elapsed in the game.

Because of service commitments, Hardy, All-American tackle John Ferraro, Gordon Gray and other stars from the 1944 team weren’t available in 1945. So USC sent one of its worst teams to the Rose Bowl. The Trojans had a 7-3 regular season record, but they weren’t a strong team. Alabama ended USC’s string of eight Rose Bowl victories by winning, 34-14.

The war ended in 1945, and 1946 was the start of an unusual era in American college football. Servicemen who played for schools before the war, trainees who played during the war and incoming freshmen all were competing for positions now.

USC had a disappointing 6-4 record in 1946, but in 1947 the Trojans took charge of the PCC again. But the Trojans had peaked too soon. They struggled even while winning, including a 6-0 victory over UCLA that clinched the Rose Bowl bid. Then, Notre Dame, destroyed USC, 38-7, before 104,953 fans—the largest crowd ever to see a game at the Coliseum, before or since. The Trojans were humiliated again as mighty Michigan dealt USC then its worst defeat in the school’s history, 49-0, in the 1948 Rose Bowl game.

USC had respectable records of 6-3-1 in 1948, including an upset 14-14 tie with unbeaten Notre Dame, and 5-3-1 in 1949. When the Trojans slipped to 2-5-2 in 1950, one of the worst records in the school’s history, Cravath was asked to resign. It was his only losing season and his overall record was a creditable 54-28-8 (.644).

* * *

USC didn’t have to look far for its new coach: he was right on campus.

Jesse T. Hill had become USC’s track coach when Dean Cromwell retired in 1949. Hill had been one of the school’s best all-around athletes. He played fullback for Howard Jones in 1928-29. He lettered three years, 1927-1929, on the track team as a broad jumper and was the first Trojan ever to better 25 feet in the event. He didn’t report for baseball until his senior year at USC, but he was the league’s leading hitter with a .389 average. He played major league baseball for the Yankees, Senators and Athletics and he retired with a 10-year batting average (majors and triple-A) of .306.

Like Gloomy Gus Henderson, Hill never achieved the acclaim as football coach that he deserved. He coached from 1951 through 1956 until he was promoted to athletic director and he had a 45-17-1 record, including two Rose Bowl appearances, a 7-0 win over Wisconsin in 1953 and a 20-7 loss to Ohio State in 1955. The win over Wisconsin was the first by a PCC team since the 1947 pact with the Big Ten.

It was under Hill’s regime that USC coverted to a multiple offense, single wing and “T,” to take advantage of the talents of Frank Giftord, who was a reserve “T” quarterback and defensive back under Cravath in 1949 and 1950.

Old Trojans still say it’s a shame that Gifford was limited to only one season, his senior year in 1951, as a tailback. Otherwise, the versatile athlete who went on to become an All-Pro with the New York Giants and then gain greater fame as a television sportscaster would be mentioned in the same breath with O.J. Simpson and other famous USC tailbacks. As it was, Gifford had an outstanding 1951 season, compiling 1,144 yards in total offense, 841 by rushing.

The Trojans finished with a 7-3 record in 1951, and in 1952 Notre Dame spoiled what was otherwise a perfect USC season (10-1) by winning, 9-0. USC finished the year by beating Wisconsin in the Rose Bowl.

Hill had records of 6-3-1 in 1953, 8-4 in 1954, 6-4 in 1955 and 8-2 in 1956 before he replaced the retiring Bill Hunter as athletic director.

There were some outstanding USC players in the early 50s, including Gifford, Pat Cannamela, Lindon Crow, Elmer Wilhoite, Jim Sears, an offensive threat who made All-American in 1952 as a defensive back, Al Carmichael, Bob Van Doren, Leon Clarke, Lou Welsh, George Timberlake, Aramis Dandoy, C.R. Roberts, Marv Goux—and Jon Arneft.

Arnett was one of the most exciting runners ever to play for USC. He was USC’s leading rusher in 1954 and 1955 with 601 and 672 yards on a total of only 237 carries. Arnett played only half a season in 1956 as a senior because of PCC penalties levied against athletes from USC, UCLA, California and Washington for taking payments in excess of what the conference allowed for living expenses.

Other players who were juniors in 1956 lost their eligibility for the 1957 season. C. R. Roberts, an explosive fullback, who rushed for a then-school record of 251 yards against Texas in 1956, was one of the players affected.

The scandals not only scarred the players but led to the dissolution of the Pacific Coast Conference in 1959. A new league, the Athletic Association of Western Universities (AAWU), was formed with USC, UCLA, California, Washington and later Stanford as the member schools. It wouldn’t be until 1964 that all of the Northwest schools would become reunited with the Big Five in the Pacific-8, which is now the Pac-l0.

It was hardly a time for a new coach to take over at USC. But Don Clark, captain of the 1947 Trojans, a star lineman with the San Francisco 49ers and an assistant under Hill, was persuaded to take the job despite the fact that the PCC had put severe restrictions on USC’s recruiting the previous two years. It is understandable why the Trojans had their worst record, 1-9, in the school’s history in 1957.

Clark tried to generate enthusiasm with a new “go-go-go” hurry-up offense. When he was able to recruit again—getting players like the McKeever twins, Mike and Marlin—the Trojans made a comeback. They were 4-5-1 in 1958 and 8-2 in 1959, losing to UCLA and Notre Dame in the last two games.

Then Clark walked away from the job. He went out as a winner and applied the same success formula to the family business—Prudential Overall Supply.

So USC was without a coach on the threshold of the 60s. The most ardent Trojan fan couldn’t imagine that the next coach would elevate the school to the national prominence that had not been attained since the days of Howard Jones.

* * *

Intelligent. Witty. Flippant. Quick-tempered. Moody. Aloof. Charming. Introverted. John McKay is all of these things—and more. To those who knew him best, the former USC coach was and is an enigma. But his friends and detractors generally agree that he’ll be remembered as one of the outstanding college coaches ever.

Not only did he restore USC to its elite status, but he also had more influence on the way offensive football is played at the college level than any other coach in his time.

It was McKay who modernized the “I” formation with the tailback standing up in the backfield some seven yards deep, with the vision to scan the defense and with the potential to strike at almost any point along the line.

When you talk about tailbacks, you’re talking about USC—such glamour runners as Heisman Trophy winners Mike Garrett, O.J. Simpson, Charles White and Marcus Allen, plus Clarence Davis, Anthony Davis and Ricky Bell.

McKay was innovative, but more important than that, he was a winner. He won four national championships (1962, 1967, 1972, 1974) during his 16 years at USC (1960-75). His teams won nine Pacific-8 titles and finished in the nation’s top l0 on nine occasions. He had a career record of 127-40-8 (.749), putting him in the same class with Jones (.750).

The Rose Bowl became almost USC’s second home during McKay’s tenure. His teams made eight New Year’s Day appearances in Pasadena, winning five and losing three.

There was an exciting quality about McKay’s teams and some of the most memorable games in USC history were played in the 60s and 70s: The 42-37 victory over Wisconsin in the 1963 Rose Bowl. The 20-17 win over Notre Dame in 1964, the game that deprived the Irish of the national championship. The 21-20 squeaker over UCLA in 1967 with Simpson sprinting 64 yards for the clinching touchdown. A final-minute 14-12 conquest of the Bruins and 26-24 over Stanford, both in 1969, and again over Stanford in 1973, 27-26. The amazing 55-24 rout of Notre Dame in 1974 after the Trojans trailed, 24-6, at halftime. The late, 18-17 victory over Ohio State in the 1975 Rose Bowl.

USC is identified with its tailbacks but rival coaches say it was the strength and mobility of McKay’s offensive lines that enabled Simpson & Company to run to daylight.

USC had more than its share of All-Americans and talented players during the McKay era: wide receivers Hal Bedsole, Lynn Swann and Bobby Chandler; tight end Charles Young; linebackers Damon Bame, Adrian Young, Charles Weaver, Jimmy Gunn, Willie Hall and Richard Wood; defensive end Tim Rossovich; offensive tackles Ron Yary, Marvin Powell, Sid Smith and Pete Adams; defensive backs Mike Battle and Artimus Parker; quarterbacks Mike Rae, Jimmy Jones and Pat Haden; and fullbacks Sam (Bam) Cunningham and Ben Wilson.

During the 40s and 50s, the USC-Notre Dame series had become one-sided, distinctly favoring the Irish. But McKay, after a tentative start, turned things around. He was shut out by the Irish his first two seasons, 1960 and 1961, and in 1966 Notre Dame embarrassed USC, 51-0, the worst defeat in Trojan history. McKay lost only once to Notre Dame the next nine seasons (two ties). When he left USC for Tampa Bay of the NFL after the 1975 season, he had established an 8-6-2 record against the Irish.

McKay played freshman football at Purdue in 1946, then transferred to Oregon the next year, where he was an All-Coast halfback. He stayed on as an assistant at Oregon, but when an opening developed on Don Clark’s staff in 1959, Clark hired McKay. It was the most fortuitous decision of McKay’s career. Clark resigned after the 1959 season and he recommended McKay for the USC job.

Now USC football was in the hands of a virtually unknown assistant coach and his debut was hardly auspicious. He lost his 1960 opener to Oregon State, 14-0, and struggled through a 4-6 season. Injuries, graduation losses and an inordinate number of slow-footed backs hindered the Trojans. Alumni were already grumbling about McKay when the new USC coach upset UCLA, 17-6, near the end of the season.

The record was not much better in 1961, 4-5-1, but McKay was already experimenting with the “I” formation. He moved Willie Brown, a flanker, to tailback, and Brown responded with a 93-yard touchdown run to beat SMU. Then, the following week against Iowa, USC had its first explosive offensive game under McKay. After trailing, 21-0, the Trojans rallied for 34 points. They lost in the final minute, 35-34, when McKay, not willing to settle for a tie, opted for the two-pointer and failed. He would lose other games by going for two points, but he would also win a Rose Bowl game and a share of the national championship with a successful two-point try. McKay saw no sense in ties; he played only to win.

In 1962 it all came together for McKay. He had benefited from recruiting, refined the “I” and borrowed the Arkansas defense from Frank Broyles. USC had speed on both offense and defense, two fine quarterbacks in Pete Beathard and Bill Nelsen, the versatile Willie Brown at tailback, strong Ben Wilson at fullback and wide receiver Hal Bedsole, a big man (6-5, 220), who could fly

The 1962 team had a perfect 11-0 record to win the national championship. In its 10 regular season games, USC outscored the opposition, 219-55, and held eight opponents to seven points or less.

The best and most thrilling aspect of the season was the 1963 Rose Bowl game with Wisconsin. The Trojans built what seemed an almost insurmountable lead, 42-14. They almost lost the game when Wisconsin quarterback Ron VanderKelen completed 18 of 22 passes in the fourth quarter. 33 of 48 in the game for 401 yards, in a remarkable near-comeback. Final score: USC 42, Wisconsin 37.

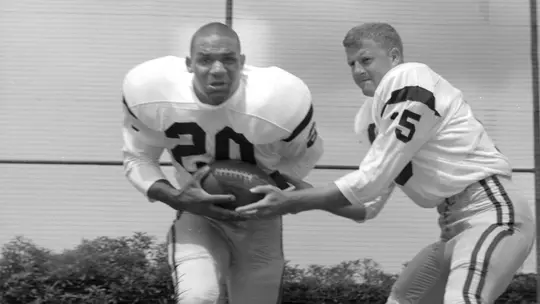

The 1963 season is notable for the debut of the first of McKay’s great tailbacks—Mike Garrett, a runner with speed and power who became USC’s first Heisman Trophy winner in 1965. McKay said it’s a shame that Garrett never got an opportunity to play in the Rose Bowl during his three seasons at USC. The Trojans had respectable records—7-3 in 1963 and again in 1964 and 7-2-1 in 1965—but losses to Washington and UCLA kept them from Pasadena.

USC just missed getting to the Rose Bowl in the mid-60s, but there was that shining moment in 1964 when the Trojans shocked Notre Dame right out of a national championship. The unbeaten Irish were on their way to a title, leading the Trojans, 17-0, at halftime. But the Trojans rallied to win, 20-17, on quarterback Craig Fertig’s touchdown pass to wide receiver Rod Sherman.

USC got to the Rose Bowl in 1966, but McKay doesn’t have pleasant memories of that season. The Trojans lost their final three games—UCLA, 14-7; Notre Dame, 51-0; and Purdue in the Rose Bowl, 14-13, when McKay lost another two-point gamble.

The next year, 1967, became significant for two reasons: one, a junior college transfer from San Francisco named Orenthal James Simpson was the new tailback. Two, the Trojans were on their way to three winning years in which they would have a combined 29-2-2 record, win the national championship and finish second and third in wire service rankings, and make three straight visits to the Rose Bowl.

When USC won its first national title under McKay in 1962, it was accomplished under one-platoon rules. In 1967 the two-platoon system was back and USC was even stronger. The incomparable Simpson averaged 154 yards a game rushing, including a single game high of 235 yards. McKay had one of his best defensive units, which allowed only 87 points.

And 1967 was the year that the team broke the South Bend jinx. Notre Dame hadn’t lost to USC at home since 1939 but Simpson’s running and a ball-hawking defense that included seven interceptions retired some old ghosts, 24-7.

There was also the showdown game with crosstown rival UCLA. The Bruins were the nation’s top-ranked team at the time. The Trojans had held the No.1 position earlier, but had slipped to third the previous week after being upset by Oregon State, 3-0, on a muddy field at Corvallis. The lead changed hands four times. UCLA spurted ahead, 20-14, in the fourth quarter behind Gary Beban, the Heisman Trophy winning quarterback. Then Simpson found daylight and sprinted 64 yards to a touchdown and a national championship.

After that, even the Rose Bowl was anticlimactic. Indiana was dominated by USC, 14-3.

The next two years, USC got another nickname—the Cardiac Kids; the team won or tied 12 times with fourth-quarter comebacks.

In 1968, Simpson carried the ball 383 times, an average of 35 carries a game, and gained 1,880 yards, an average of 4.9 yards a carry, on his way to winning the Heisman Trophy.

USC came into the Rose Bowl against Ohio State that season with a 9-0-1 record. Despite an 80-yard touchdown run by Simpson, the Buckeyes took advantage of Trojan turnovers to win, 27-16.

The 1969 team had a 10-0-1 record, climaxing the season with a 10-3 victory over Michigan in the Rose Bowl. But the second edition of the Cardiac Kids was often maligned because they didn’t win by impressive margins. The fabulous Juice was gone and the Trojans had new personalities—sophomore quarterback Jimmy Jones, tailback Clarence Davis and a defensive line known as the Wild Bunch.

Jones could misfire on eight straight passes and then become accurate in the final minutes. Davis is now known as the “forgotten” USC tailback because his career followed those of Garrett and Simpson. Davis led the Trojans in rushing in 1969 and 1970, gaining 1,351 and 972 yards.

The name, Wild Bunch, was inspired by the current movie of the same name. The group was composed of ends Jimmy Gunn and Charles Weaver, tackles Al Cowlings and Tody Smith, and middle guard Bubba Scott. Gunn and Cowlings were All-Americans in 1969. Weaver was so honored in 1970.

The Cardiac Kids were at their heart-stopping best in a 26-24 victory over Stanford. Late in the game, USC surged back behind Jones’ passing and Davis’ running to set up Ron Ayala’s 34-yard field goal with no time remaining.

The 1969 USC-UCLA game is considered one of the most dramatic of the series. Both teams were unbeaten with 8-0-1 records. The Wild Bunch gave UCLA quarterback Dennis Dummit a beating, but UCLA took the lead, 12-7 with 5 minutes left. Then, Jones, 0 of 9 passing in the first half, began to hit his receivers. A pass interference penalty against UCLA on an apparent fourth-down incompletion gave Jones a reprieve. He fired a 32-yard touchdown pass to Sam Dickerson deep in the end zone—and USC had pulled it out, 14-12, with 1:32 to play.

USC was 6-4-1 in 1970 and matched that in 1971. Winning years in some books, but not at USC.

McKay became conscious in 1970 that he needed faster and more talented players. By 1972 he had the right blend of experience and youth. He also had one of the greatest teams in the history of college football.

This was a team without an apparent weakness. It had a 12-0 record, scored 467 points, averaged 432 yards a game, never trailed in the second half, restricted opponents to an average of only 2.5 yards per rush and didn’t permit a run longer than 29 yards.

McKay had two quality quarterbacks, senior Mike Rae and sophomore Pat Haden; an outstanding sophomore tailback, Anthony Davis, who became a starter at midseason; a high diving, excellent blocking fullback, Sam (Bam) Cunningham; tight end Charles Young and offensive tackle Pete Adams, both All-Americans; skilled defensive players like tackles John Grant and Jeff Winans and Richard (Batman) Wood, a sophomore All-American linebacker who could run the 40 in 4.5 seconds, and three fine wide receivers, Lynn Swann, Edesel Garrison and Johnny McKay, the coach’s son.

The Trojans breezed through their schedule until the regular-season ending game with Notre Dame at the Coliseum. The Irish made a game of it, and closed to within two points, 25-23, late in the third quarter. Then Anthony Davis returned a kickoff 96 yards for a touchdown. He had earlier scored on a 97-yard kickoff return. The momentum belonged to the Trojans and they won, 45-23. Davis scored six touchdowns against Notre Dame that day, the most ever by a Trojan.

To underscore that the team was clearly the best in the country, USC destroyed Woody Hayes’ Ohio State team, 42-17, in the Rose Bowl. Cunningham sky-dived for four touchdowns, Rae completed 18 of 25 passes for 229 yards with no interceptions and Davis slashed for 157 yards, including a 20-yard TD run that broke the game open.

The Trojans were undisputed as No.1. For the first time in collegiate history, USC got every first-place ballot in the final AP and UPI polls.

McKay had lost 12 regulars from his 1972 team when the 1973 season opened. Still, the Trojans responded with a 9-2-1 record and another appearance in the Rose Bowl (Ohio State won, 42-21).

McKay believed that he had one of the strongest teams in the country at the outset of the 1974 season. Haden and Davis were both seniors. The team was generally experienced.

The Trojans were shocked by Arkansas, 22-7, in the opener at Little Rock, and weren’t impressive at times, especially at mid-season when they were tied by California, 15-15. But then they got rolling, leading to one of the most remarkable games ever played. The Trojans, apparently beaten by Notre Dame and trailing, 24-0, in the first half, rallied for 35 points in the third quarter, scored more in the fourth quarter and won, 55-24. Anthony Davis returned the second-half kickoff 102 yards for a touchdown to get the roll started, the sixth of his career, breaking the existing NCAA record.

The Trojans, with a flair for the dramatic, had not run out of comebacks. In the 1975 Rose Bowl game, USC trailed Ohio State, 17-10, with minutes left to play. Haden teamed with Johnny McKay on a 38-yard touchdown pass. Coach McKay went for the two-point conversion try. Haden threw a low, accurate pass to Shelton Diggs for an 18-17 victory. The pass was the biggest play of the year because Alabama had lost to Notre Dame on New Year’s night in the Orange Bowl and USC was elevated to the No.1 spot in the final UPI poll.

In 1975, USC won its first seven games. But Troy wasn’t as formidable as its record indicated—and there was something else. McKay announced before his team was to play at California in game eight that he would be leaving USC at the end of the season to coach the NFL expansion team in Tampa Bay.

McKay was in the dual role of athletic director and football coach. He had become weary of the politics of college athletics and the recruiting grind after 16 years. And there was precious little more that he could accomplish at the college level. The most compelling reason to leave USC, however, was the lifetime security of the Tampa Bay offer.

McKay’s decision had an immediate adverse effect on his team, which lost four straight conference games. Although USC had a disappointing 7-4 regular season record and was out of the Rose Bowl race even before the UCLA game, McKay still went out as a winner. The Trojans played in the Liberty Bowl in Memphis and pulled off a mild upset by defeating Texas A&M, 20-0.

* * *

Howard Jones won his last national championship in 1932. John McKay won his first in 1962. That’s a 30-year drought between legendary coaches. USC wouldn’t have to wait that long after McKay resigned.

John Robinson, McKay’s replacement, not only maintained the winning Trojan tradition, he added a new dimension to the USC football program.

Robinson went 67-14-2 (.819) in his first seven-year stint at USC (1976-1982). He won a national championship in 1978. His teams finished second in the final wire service polls twice, in 1976 and in 1979. He won three Rose Bowls (1977,1979,1980) and a Bluebonnet Bowl game (New Year’s Eve, 1977).

As a tactician, he retained the best from McKay—the formation and tailback-oriented offense along with a sound defense—while establishing the quarterback as a more important figure in his offense.

McKay’s best teams were balanced offensively (running and passing), but, in 1975, when USC slumped, the poor play of quarterback Vince Evans was a contributing factor. Evans was much improved under Robinson in 1976. Robinson was also responsible for the improvement of Rob Hertel in 1977. It was in 1978 and 1979 that the quarterback, Paul McDonald, really came into a position of eminence in the USC offense, rivaling that of the tailback, Charles White.

Robinson, like McKay, was a virtually unknown assistant when he was named USC’s coach. He was a reserve end on Oregon’s 1957 Rose Bowl team and he stayed at his alma mater for 12 years as an assistant before becoming McKay’s offensive coordinator from 1972 through 1974. He left USC in 1975 to join the Oakland Raiders as an offensive assistant coach.

Robinson’s first night as a head football coach was a nightmare. That was Sept. 11, 1976, when Missouri shocked Robinson’s Trojans, 46-25, in the opener.

But the game was hardly a harbinger for the season. The Trojans got their act together and won their next eight games to set up another Rose Bowl-deciding game with UCLA, unbeaten and ranked No. 2 in the country under new head coach Terry Donahue. USC won, 21-14.

Ricky Bell was the latest model off the USC tailback assembly line that season. He had broken O.J. Simpson’s single season rushing record the previous year, gaining 1,957 yards on 385 carries.

Bell didn’t fit the mold of a typical USC tailback. Garrett, Clarence Davis, Anthony Davis and, later, White, were short, stocky types. Bell, a former fullback and linebacker, was a battering, bruising runner with good speed for a big man. He gained 1,433 yards for the season to become USC’s No.2 all-time leading rusher behind Anthony Davis, 3,724 to 3,689.

After the 1976 win over UCLA, USC beat Notre Dame, 17-13, the next week and then the Trojan defense completely destroyed powerful Michigan in the Rose Bowl. The Wolverines were the nation’s leading scoring (39 points average) and rushing team (448 yards), but they could score only six points and rush for 217 yards as USC won, 14-6, without Bell.

Bell was knocked unconscious on USC’s first series. White, who would go on to become the school’s most prolific rusher, filled in with 114 yards on 32 carries. Evans completed 14 of 20 passes for 181 yards, scored a touchdown on a one-yard keeper and was named Player of the Game. Robinson became the first rookie head coach from the Pac-8 to win the Rose Bowl game in 61 years.

Bell, safety Dennis Thurman, defensive tackle Gary Jeter and offensive tackle Marvin Powell got All-American recognition. USC finished with an 11-1 record and a No. 2 national rating behind undefeated Pittsburgh.

Expectations were high for 1977. The Trojans started fast, winning their first four games and moving to the top of the rankings. Alabama snapped USC’s 15-game unbeaten streak with a 21-20 victory at the Coliseum and the Trojans suddenly became an inconsistent team. They lost three of their next five games, including an embarrassing 49-19 setback to Notre Dame at South Bend, where the Irish switched from blue to green jerseys before the game to get a psychological advantage.

The Trojans were out of the Rose Bowl running by the time they met UCLA. But it was an important game for the Bruins. If they beat USC, they would get the Rose Bowl bid; a loss would send Washington to Pasadena. In one of the most exciting games of the city series, the Bruins were leading, 27-26, with only a few minutes remaining. Then, Frank Jordan kicked a 38-yard field goal with two seconds left, kicking UCLA out of the Rose Bowl, 29-27.

USC got a consolation prize, a Bluebonnet Bowl bid against Texas A&M at Houston’s Astrodome. It was a wild offensive party on New Year’s Eve. USC gained 620 yards rushing and passing; A&M gained 519. USC won, 47-28.

For a change, USC wasn’t highly ranked in the 1978 preseason polls. Nor were the Trojans the consensus favorite to win the newly-expanded Pacific-10 with the addition of Arizona and Arizona State.

USC opened with lackluster wins over Texas Tech and Oregon. No. 1-ranked Alabama was waiting for USC in Birmingham. The Trojans, with tailback Charles White who was now a junior gaining 199 yards on 29 carries, toppled Alabama, 24-14. USC didn’t let down the next week against Michigan State, the Big Ten co-champion. The Trojans buried the Spartans, 30-9. USC seemed unbeatable then, but it was walking into a trap at Tempe. Arizona State surprised USC, 20-7. The Trojans couldn’t afford to lose another game if they expected to get to the Rose Bowl. They didn’t.

The Trojans had the Rose Bowl bid but if they were to stay in contention for the national championship, they had to beat their old rival, Notre Dame, the following week at the Coliseum.

USC had Notre Dame reeling, leading them, 24-6, after three quarters. The Irish made a comeback to rival any in the school’s illustrious history. Incredibly, Notre Dame scored three touchdowns in the fourth quarter to take a 25-24 lead with 46 seconds remaining. There was time enough for USC to make an even more amazing comeback. Jordan, who had kicked a 38-yard field goal with two seconds left to beat UCLA in 1977, booted a 37-yard field goal with two seconds remaining to shock Notre Dame, 27-25.

It was on to the Rose Bowl for USC, where the Trojans scored a 17-10 win over Michigan. USC went into the game as the nation’s third-ranked team, behind unbeaten Penn State and once-beaten Alabama, in both wire service polls. After Alabama beat Penn State in the Sugar Bowl, the Tide won the national championship in the AP poll and USC barely won in the UPI balloting.

If USC was overlooked in preseason ratings in 1978, they made up for it in 1979.

The Trojans seemed awesome. They were coming off a 12-1 season, a share of the national championship and White and McDonald, now seniors, represented the best one-two offensive punch in college football. Besides White and McDonald, Robinson had such skilled players as offensive tackle Anthony Munoz and guard Brad Budde, both All-American prospects; wide receiver Kevin Williams, tight ends Hoby Brenner, James Hunter and Vic Rakhshani; defensive linemen Myron Lapka, Ty Sperling and Dennis Edwards; linebackers Dennis Johnson and Larry McGrew; and two of the nation’s best safeties, Ronnie Loft and Dennis Smith.

USC won its first five games, but then lost its No.1 ranking in an improbable manner. Stanford was the spoiler. The Cardinals stunned USC with 21 unanswered points in the second half and the game ended in a tie, 21-21. USC had had its letdown for the season, but it didn’t falter again.

The Trojans were back in the Rose Bowl, this time against Ohio State. With 5:21 to play, the Buckeyes led, 16-10, and the Trojans were in deep trouble at their own 17-yard line. White, who was already the runaway winner in the Heisman Trophy balloting, simply ran through Ohio State. The Trojan tailback gained 71 yards of an 83-yard stay-on-the-ground assault climaxed by his diving touchdown inches away from the goal line. The successful conversion enabled USC to preserve its unbeaten record, 11-0-1. The Trojans wound up as the nation’s No. 2 team in both polls.

White and McDonald had superb seasons. White was the nation’s leading rusher in 1979. He wound up his regular season career with 5,598 yards—second highest total in NCAA history. McDonald set 17 NCAA, Pac-l0 and school passing records. All-American guard Brad Budde won the Lombardi Award as the nation’s best lineman and linebacker Dennis Johnson also won All-American honors.

The decade of the ’80s marked the emergence of still another tailback to carry on the legacy of excellence that is inherent with the USC football program.

Marcus Allen, who had served his apprenticeship as Charles White’s fullback in 1979 (gaining 649 yards and scoring eight touchdowns), was now prepared to assume the demanding responsibility as tailback in the I formation. Allen was a reserve tailback in 1977 as a freshman, with only limited experience at the position considering that he was a quarterback and defensive back in high school.

The graduation loss of Paul McDonald left John Robinson without an experienced quarterback in 1980, so USC was one dimensional on offense, student body left and right.

Despite his inexperience at the position and a limited passing game, Allen still managed to gain 1,563 yards, and catch 30 passes. He also showed his versatility by completing the only two passes he threw, one for a 36-yard touchdown.

The Trojans, who were ineligible to play in a bowl game due to conference sanctions, finished with an 8-2-1 record, losing to Washington, the Rose Bowl representative, and narrowly to UCLA, 20-17—the Trojans’ first loss to the Bruins in Robinson’s five seasons as USC’s coach.

Three Trojans, defensive back Ronnie Loft, offensive tackle Keith Van Horne and offensive guard Roy Foster were recognized as All-Americans.

Allen had a productive first season as USC’s tailback. Still, it wasn’t an indication of what he would accomplish in 1981. A more confident, skilled player now, his statistics were awesome even though he was a marked man. Allen was virtually the USC offense as he gained 2,342 yards through 11 regular season games, an NCAA mark, while averaging a record 212.9 yards per game. His record-breaking season was validated as he became the fourth Trojan tailback to win the Heisman Trophy.

Even though USC won its first four games, including a thrilling last-second 28-24 victory over Oklahoma on national TV, an upset loss to Arizona, 13-10, and a 13-3 setback to Washington in Seattle prevented the Trojans from going to the Rose Bowl. However, USC ended the regular season with a 22-21 victory over UCLA as nose guard George Achica blocked a late Bruin field goal try to preserve the win.

The Trojans didn’t fare so well in the Fiesta Bowl, where they were dominated by Penn State, losing, 26-10, to finish with a 9-3 record. Allen was a unanimous All-American with Foster repeating and linebacker Chip Banks getting equal recognition.

Because of NCAA and conference sanctions, USC was ineligible to participate in any bowl games the next two seasons.

USC still had a respectable 8-3 season in 1982 despite the loss of Allen and an injury-decimated tailback corps.

It was in the week preceding the 1982 Notre Dame game that Robinson disclosed that he was leaving USC as football coach to become a senior vice president in the school’s administration. He wouldn’t remain at that position long, though, leaving USC soon after to become the Rams’ coach.

So the theme for the Notre Dame game was “Win One for the Fat Guy,” pertaining to Robinson’s girth and his popularity. The Trojans did just that, 17-13, with tailback Michael Harper scoring the winning and controversial touchdown in the closing minutes. It was argued that Harper didn’t have the ball when he sky-dived over a pile at the goal line.

Achica and offensive linemen Don Mosebar and Bruce Mathews were named All-Americans.

* * *

The successful Robinson, who had coached USC to three Rose Bowl wins and a national championship in 1978, was replaced by Ted TolIner, who had joined the USC staff in 1982 as offensive coordinator. However, although nobody knew it then, it wouldn’t be the last time Trojan fans saw Robinson.

Tollner’s first season wasn’t auspicious as the Trojans slumped to a 4-6-1 record, the first losing season in 22 years. Their 27-6 loss to Notre Dame was the start of a frustrating streak—13 consecutive years without a win over the Irish. Center Tony Slaton was an All-American in 1983.

The Trojans rebounded in 1984, winning seven straight Pac-10 games and clinching the Rose Bowl bid a week before the end of the conference season with a 16-7 victory over Washington. Tollner had a defensive team featuring All-American linebackers Jack Del Rio and Duane Bickett, while a fiery JC transfer, quarterback Tim Green, who replaced injured Sean Salisbury, provided leadership on offense. The Trojans had a letdown after beating Washington, losing to UCLA and Notre Dame. But Tollner’s team regrouped to beat Ohio State, 20-17, in the Rose Bowl for a 9-3 record.

Although USC was favored to repeat as conference champs in 1985, the Trojans had a 6-6 season, ultimately losing to Alabama, 24-3 in the Aloha Bowl.

The Trojans started fast in 1986, winning their first four games. Then, USC was upset by Washington State, 34-14, and lost to Arizona State, 29-20, before winning three straight conference games. But the Trojans finished on a sour note, losing to UCLA, 45-25, and Notre Dame, 38-37. Tollner was then fired, the first USC coach to be terminated since Jeff Cravath in 1950. Tollner’s four-year record was 26-20-1.

Tollner was a lame duck when USC lost to Auburn, 16-7, in the Citrus Bowl that concluded a 7-5 season. Offensive guard Jeff Bregel and safety Tim McDonald, All-Americans in 1985, did so again in 1986.

* * *

A day following the Jan. 1 Citrus Bowl, Arizona coach Larry Smith was named as Tollner’s replacement. Smith had revived Arizona’s program in his seven years there, winning 70% of his games in his last four seasons. He also coached Arizona to a startling upset over No.1 ranked USC in 1980 and had beaten rival Arizona State five straight times.

The Trojans had a roller coaster season in 1987, Smith’s first year as coach. Michigan State beat USC, 27-13, at East Lansing in the opener and Oregon upset USC, 34-27, at Eugene at midseason to imperil USC’s Rose Bowl aspirations. But the Trojans rebounded to beat Washington, 37-23, at Seattle when a loss would have meant virtual elimination from the Rose Bowl race. The Trojans kept winning behind quarterback Rodney Peete, who was to break every meaningful USC passing record, and tailback Steven Webster, a 1,000-yard rusher.

As it has so many times in the past, the Rose Bowl deciding game paired the Trojans against the Bruins. But USC, an 8 1/2 point underdog, prevailed, 17-13, getting the winning touchdown on Peete’s 33-yard pass to receiver Erik Affholter, who juggled the ball in the corner of the end zone. Peete provided the play of the game late in the first half, when he ran down UCLA’s Eric Turner, who had intercepted Peete’s pass and was apparently headed for a TD that would have provided UCLA with a 17-0 halftime lead.

USC was back in the Rose Bowl only to lose to Michigan State again, 20-17. Offensive lineman Dave Cadigan was selected an All American.

The 1988 campaign began in glorious fashion for the Trojans. USC was celebrating its athletic centennial and the football team did its part, starting off 10-0 and rising to No. 2 in the rankings. With its second consecutive Rose Bowl berth clinched by virtue of a 31-22 win over UCLA (Peete was hospitalized all week with the measles, but came off his sickbed to lead Troy to victory), the undefeated Trojans hosted top-ranked Notre Dame. But the Irish prevailed, 27-10, and USC couldn’t recover in the Rose Bowl, falling to Michigan, 22-14, as Smith lost to his former boss, Bo Schembechler (who he served under at Miami of Ohio and Michigan).

Peete, who finished second in the Heisman voting and set a USC season and career passing records, was an All-American, along with Affholter, safeties Mark Carrier and Cleveland Colter and defensive tackle Tim Ryan.

USC’s 1989 season was supposed to open in historic fashion—against Illinois in the Glasnost Bowl in Moscow of the Soviet Union, but those plans had to be scratched because of contractual difficulties with the game’s organizers (the game was played in the Coliseum and the Illini won, 14-13). The Trojans then won eight of their next nine games, including a dramatic 18-17 comeback win at Washington State when freshman quarterback Todd Marinovich—whose father, Marv, captained the 1962 USC squad and whose uncle, Craig Fertig, was USC’s 1964 captain—passed USC 91 yards down the field in 18 plays at game’s end. Troy’s only loss during that span was 28-24 at Notre Dame (USC also tied UCLA, 10-10). USC, which finished 9-2-1, made it to the Rose Bowl for the third year in a row and the third time was the charm for Smith as he beat No. 3 Michigan, 17-10, in Schembechler’s last game as Wolverine coach. Tailback Ricky Ervins, who rushed for 1,395 yards in 1989, ran 14 yards for the game-winning TD with 1:10 to play to earn Rose Bowl MVP honors.

Carrier and Ryan repeated as All-Americans in 1989 (Carrier also won the Thorpe Award as the nation’s top defensive back), while linebacker Junior Seau and offensive guard Mark Tucker also won All-American acclaim.

USC’s Rose Bowl streak ended in 1990, although the 8-4-1 Trojans did play in a bowl that season, narrowly losing to Michigan State (17-16) in the John Hancock Bowl. The season’s highlight was the UCLA game, the highest-scoring and perhaps most thrilling game in the storied crosstown rivalry. The game, won by USC, 45-42, featured a 42-point fourth quarter with four lead changes, capped by Marinovich’s 23-yard game-winning pass to Johnnie Morton with 16 seconds to go. Linebacker Scott Ross was a 1990 All-American and tailback Mazio Royster rushed for 1,168 yards.

The Hancock Bowl loss—marked by a sideline shouting match between the stern disciplinarian Smith and the free-spirited sophomore Marinovich, who soon after left for the NFL—signaled the beginning of the end for Smith’s tenure at USC. Things quickly unraveled in 1991, as the Trojans were upset in their home opener by unheralded Memphis State, 24-10. Although USC upset No. 5 Penn State the following game, 21-10, Troy had a difficult year. The Trojans were 3-8, ending the season with six consecutive losses—including the first of an embarrassing eight in a row to UCLA—and no bowl trip.

Smith’s 1992 season started decently. Despite a tie with San Diego State in the opener and a close 17-10 road loss to top-ranked Washington, USC regrouped to win four in a row, but then disaster struck as the Trojans lost four of their last five, including 38-37 to UCLA when a potential game-winning 2-point conversion pass with 41 seconds to go fell incomplete (Troy had a 14-point fourth quarter lead) and 24-7 to upstart Fresno State in the Freedom Bowl. USC, fielding its 100th football team, finished 6-5-1, despite featuring a pair of All-Americans in electrifying wide receiver/return specialist Curtis Conway (who set the school’s career kickoff return record) and offensive tackle Tony Boselli. So, just three seasons after directing the Trojans to three straight Rose Bowls, Smith was fired…and a familiar face returned to Troy.

* * *

After a successful nine-year run coaching the Rams, in which he made the playoffs six times, and then a year off spent as a television analyst, John Robinson returned to USC in 1993 in hopes of restoring the football program’s past glory.

He had an immediate impact, as his first team tied for first place in the Pac-10 (UCLA received the Rose Bowl bid because it beat the Trojans, 27-21). Like in his first stint at Troy, Robinson lost his opener (31-9 to North Carolina). He then lost three road games to Top 15-ranked teams (Penn State on a failed two-point conversion attempt at game’s end, Arizona and Notre Dame), but the 8-5 Trojans did beat Washington in Seattle to end the Huskies’ 17-game home winning streak and they prevailed over Utah in the Freedom Bowl, 28-21. USC almost made it to the Rose Bowl, but for an intercepted 3-yard pass in the end zone with 56 seconds to play to preserve UCLA’s 27-21 victory. His team featured Morton, an All-American who set USC’s career receiving record with 201 catches, plus quarterback Rob Johnson (whose 3,630 passing yards was a Trojan season record) and fearsome linebacker Willie McGinest. USC played in the new-look Coliseum, where a $15-million renovation included the removal of the running track and the lowering of the field.

The 1994 season saw the return of another familiar face to USC when one-time ballboy Keyshawn Johnson transferred from a junior college. Johnson, a big, speedy receiver, was brash, loquacious and had a magnetic personality. The Trojans began 2-2, then strung together five wins in a row. Although USC lost again to UCLA, its 10-10 tie with Notre Dame did dent a long drought to the Irish (Notre Dame had won the previous 11 games). USC made a statement in the Cotton Bowl with its 55-14 win over Texas Tech to finish 8-3-1, and Johnson also stood out in that game as he caught eight passes for 222 yards with three touchdowns (the yardage and TDs were Cotton Bowl records). Boselli, hampered by a knee injury in 1993, earned All-American honors again.

Amazingly, USC was able to play its games that year in the Coliseum even though the grand stadium was severely damaged in an earthquake in January of 1994 and had to undergo $93 million of repairs.

Robinson got his next team back to the Rose Bowl. The 1995 Trojans started off 6-0, then lost at Notre Dame and tied Washington in Seattle, 21-21 (Troy scored 21 unanswered points in the fourth quarter). Because of a better overall record than the Huskies, USC got the Rose Bowl bid where it defeated No. 3 Northwestern, 41-32, a Cinderella team making its first Pasadena visit since 1949. Johnson finished his brief USC career as the Rose Bowl MVP, grabbing 12 passes for a game-record 216 yards with a TD. His 102 catches that season were a school record and he ended up second on USC’s career receiving list before becoming the No. 1 pick in the 1996 NFL draft. Tailback Delon Washington rushed for 1,109 yards for the 9-2-1 Trojans.

Although USC wound up 13th in the final 1994 AP poll and 12th in 1995, that 1995 campaign was the peak of Robinson’s second stint guiding USC. He couldn’t take USC any higher; in fact, his Trojans leveled out the next two years.

In 1996, Troy went 6-6, losing a pair of heartbreakers—both in two overtime periods (the NCAA instituted the tiebreaker beginning with the 1995 bowl contests). First, USC lost at Arizona State, 48-35, then fell to UCLA, 48-41, as the Bruins erased a 17-point deficit in the final 6:12 of the fourth quarter. The bright spot of the season was a 27-20 season-ending overtime win over Notre Dame in the Coliseum, breaking USC’s 13-game non-winning streak to the Irish.

In 1997, for the second year in a row, USC didn’t play in a bowl. However, the 6-5 Trojans did post their second straight win over Notre Dame, this time 20-17 on Adam Abrams’ 37-yard field goal with 1:05 to play to give USC its first victory in South Bend since 1981. USC’s 23-0 win at Oregon State was not shown on television, ending USC’s streak of 111 consecutive live telecasts. Defensive tackle Darrell Russell earned All-American honors.

Robinson, whose last two teams went 1-6 against Top 25-ranked opponents, was fired after the 1997 season.

* * *

His replacement was someone familiar with USC and its tradition of success: Paul Hackett. Hackett had been an assistant under Robinson from 1976 to 1980 and was on the Trojan staff during the 1978 national championship season. He then made his mark in the NFL as a quarterbacks coach and offensive coordinator with four teams, including the 1984 Super Bowl champion San Francisco 49ers. In his career, he had tutored the likes Joe Montana, Marcus Allen, Jerry Rice, Tony Dorsett, Charles White, Herschel Walker and Danny White.

Hackett got off to a good start, winning his 1998 opener (27-17 over Purdue) to become the first Trojan head coach to win his debut since Jess Hill in 1951. USC went 8-5, shut out Notre Dame, 10-0 (the Irish’s first shutout since 1987), and played in the Sun Bowl. Chris Claiborne was an All-American and became USC’s first winner of the Butkus Award as the nation’s top linebacker.

The 1998 season also had a sad note to it, as 91-year-old “Super Fan” Giles Pellerin died at the UCLA game while viewing his 797th consecutive Trojan game, home and away. His streak dated to 1926; he had seen every USC-UCLA and USC-Notre Dame game ever played before his passing.

USC looked like it was going to take another step up in 1999, starting off 2-0. But quarterback Carson Palmer broke his collarbone in the third game and was sidelined for the season, and Troy dropped six of its next seven contests (the win was at home against Oregon State, USC's 1,000th game). Although they missed out on a bowl, the 6-6 Trojans rebounded by winning their last three games, including 17-7 over UCLA to snap an eight-game losing streak to the Bruins. All six of USC’s losses were by 10 points or less. Tailback Chad Morton rushed for 1,141 yards.

Things didn't improve in 2000, as the new millennium unfolded. Although USC began 3-0 and climbed to No. 8 in the AP poll, it lost the next 5 games. Despite beating UCLA on David Bell's dramatic field goal with 9 seconds to play, the Trojans finished 5-7 overall and out of a bowl for the second consecutive year. Their 2-6 mark in the Pac-10 left them with their first-ever last place finish in conference play. Hackett was fired after the season and replaced by Pete Carroll, who came with 26 years of college and pro coaching experience (including head coaching stints with the NFL's New England Patriots and New York Jets).

Carroll's first squad in 2001 started slowly (at 1-4 and then 2-5), but rebounded by winning its final four regular-season games (and its last five Pac-10 contests), including a 27-0 home shutout over UCLA, to earn a spot in the Las Vegas Bowl. Although the Trojans finished 6-6, the losses were by a combined 29 points. Five were by five points or less (the first time that happened in a USC season), including twice when opponents kicked field goals in the final 12 seconds (once at the gun), also a USC first. Hampered by injuries to its tailback corps, the Trojans rushed for an all-time low 1,052 yards. However, safety Troy Polamalu earned All-American honors.

Then, in 2002, USC harkened back to its dominating glory days. USC closed its campaign with an 8-game winning streak (getting at least 400 yards of total offense and 30 points in each game). In fact, some said the Trojans were playing the best ball in the nation by year's end. Troy went 11-2 overall, earned a No. 4 final ranking, won a share of the Pac-10 championship (going 7-1), scored decisive wins over UCLA and Notre Dame (for the first time in the same season since 1981) and posted an impressive victory in the BCS' Orange Bowl...all while playing what was ranked as the nation's toughest schedule. It was USC's most wins and highest final ranking since 1979. The Trojans finished in the nation's Top 20 in nearly every team statistical category and led the Pac-10 in scoring offense and defense. No opposing runner gained 100 yards versus USC. Not only did Polamalu repeat as an All-American, but quarterback Carson Palmer--the Pac-10's career passing and total offense leader who set 33 USC and Pac-10 records--became Troy's fifth Heisman Trophy winner. Kareem Kelly set USC's career reception record.

That might seem like a hard act to follow, especially with the likes of Palmer, Polamalu and Kelly gone, but the 2003 Trojans exceeded expectations by going 12-1 and winning the AP version of the national championship (USC's first in 25 years). Troy won its second straight Pac-10 title and, despite being controversially snubbed for the BCS Championship Game in the Sugar Bowl, handily demolished No. 4 Michigan in the Rose Bowl.

Except for a triple overtime loss at California early on, the Trojans won each game handily. It started with a 23-0 opening shutout at Auburn and included a second consecutive sweep of the Irish and Bruins. USC scored at least 30 points in 11 consecutive games, including 40 points in 7 in a row (both Pac-10 records), en route to tallying 534 total points (another Pac-10 mark). The Trojan defense topped the nation in rushing defense and was second in turnover margin, forcing 42 turnovers and scoring 8 TDs.

Five players won All-American first team honors: quarterback Matt Leinart, wide receiver Mike Williams, defensive end Kenechi Udeze, offensive tackle Jacob Rogers and punter Tom Malone (Leinart and Williams finished sixth and eighth, respectively, in the Heisman voting). Carroll was recognized as the National Coach of the Year.

In 2004, USC left no doubt in winning a second consecutive national championship. And, unlike 2003, this title was undisputed, as USC demolished Oklahoma in the BCS Championship Game in the Orange Bowl, 55-19. Troy went 13-0 overall (a school record for victories) and became just the second team ever to hold the AP No. 1 ranking from pre-season through the entire campaign. It was only the 10th time that a team won back-to-back AP crowns. At 8-0, USC won its third consecutive Pac-10 title. The Trojans swept traditional rivals UCLA and Notre Dame for an unprecedented third year in a row. (USC's last 2 wins of 2004 were later vacated due to NCAA penalty.)

Troy was in the national Top 10 in every defensive statistical category (its total defense average was USC’s lowest in 15 years), including first in rushing defense and turnover margin and third in scoring defense. USC outscored opponents by 25.2 points (including a school-record 8 games with a margin of at least 30 points). USC played before 3 home sellouts, 7 regular-season sellouts and 8 season sellouts, all school marks. And Troy set a USC and Pac-10 record for home attendance average.

A school-record 6 Trojans (Heisman Trophy quarterback Leinart, Heisman finalist tailback Reggie Bush, defensive linemen Shaun Cody and Mike Patterson, and linebackers Matt Grootegoed and Lofa Tatupu) were named All-American first teamers.

USC came oh-so-close to winning an unprecedented third consecutive national championship in 2005, but it lost a 41-38 heartbreaker in the Rose Bowl's BCS Championship Game when Texas scored in the final 19 seconds. The loss snapped a school-record 34-game overall winning streak, as well as national records of 33 conseutive weeks as AP's No. 1 team and 16 straight wins over AP Top 25 teams. USC went 12-1 (finishing second in the polls) overall and 8-0 in the Pac-10 to win its fourth straight league title. (All of USC's wins in 2005 were later vacated due to NCAA penalty.)

However, USC ended the season having extended its streaks for wins in a Pac-10 record 27 consecutive home games, a Pac-10-record 23 straight overall Pac-10 games, a Pac-10 record 19 consecutive league home games and a school-record 15 road games in a row. The Trojans swept rivals Notre Dame and UCLA for an unprecedented fourth season in a row.

Troy’s offense was in the national Top 6 in every statistical category, including tops in total offense (579.8) and second in scoring offense (49.1), and set Pac-10 records for total offense yardage, points scored, touchdowns and PATs. The Trojans won games by an average of 26.2 points. USC became the first school to have a 3,000-yard passer (Leinart), a pair of 1,000-yard runners (Bush and fellow tailback LenDale White) and a 1,000-yard receiver (wide receiver Dwayne Jarrett) in a season. And USC was second nationally in turnover margin (+1.6). For the second year in a row, USC set Pac-10 records for total home attendance and home attendance average and school marks for overall attendance and overall attendance average. The Trojans also set school standards for the second straight year for home sellouts (4), regular season sellouts (9) and season sellouts (10).

For the second consecutive year, a school-record 6 Trojans were All-American first teamers (Bush, Leinart, Jarrett, offensive linemen Taitusi Lutui and Sam Baker and safety Darnell Bing, with Bush winning USC's third Heisman in 4 years.

But for a stunning 13-9 end-of-the-regular-season upset loss at UCLA, USC would have returned to the BCS Championship Game in 2006 for the third year in a row. The Bruin loss ended USC's NCAA record string of 63 consecutive games scoring 20 points. As it was, the Trojans--playing the nation's second most difficult schedule--ended up 11-2 on the year, beating No. 3 Michigan in the Rose Bowl, 32-18, and finishing fourth in the final polls. A fifth straight win over Notre Dame was included in the tally. Troy went 7-2 in the Pac-10 to claim an unprecedented fifth consecutive league title to go along with its fifth straight AP Top 4 finish, BCS bowl trip and 11-win season.

As 2006 concluded, the Trojans extended their Pac-10 record winning streaks for home games (33) and league home games (23), and they were ranked in the AP Top 10 for a school-record 56 games.

Jarrett set the Pac-10 record for career touchdown receptions (41) and the USC all-time mark for receptions (216). He and fellow wide receiver Steve Smith each had 1,000 receiving yards. The Trojan defense was in the national Top 25 in every statistical category, as was the other side of the ball in passing, scoring and total offense. But for the first time in the Carroll era, USC's turnover margin slipped from the previous year.